In a recent Barbados Today article, the CEO of the newly minted GovTech Barbados stated with confidence that the country is “on the brink of a sweeping digital transformation, with a particular focus on enhancing its cybersecurity infrastructure.” While the ambition is commendable, it’s crucial to examine these claims with a critical eye. As someone deeply involved in the tech sector for almost 30 years, I find several elements of this grand vision questionable at best, and potentially misleading at worst.

The ‘Conundrum’ of the Tier 3 Data Center

The government’s plan to establish a Tier 3 National Data Center sounds impressive on paper. However, this claim ignores several fundamental realities of Barbados’ infrastructure, market conditions, and human capacity.

Costs

With a monopoly electric company serving the entire island, is it even possible to achieve the redundancy and reliability required for a Tier 3 facility in a cost effective manner? Tier 3 data centers demand multiple, independent power distribution paths. In the Uptime Institute tier model, onsite power is the only reliable source of power – it is completely within the span of control of the organization, with no conflicting external entity’s profitability goals. Given the high costs of commercial power in Barbados ($0.33 per KWh – one of the highest in the world), and the even higher costs associated with operations and maintenance for onsite generated power, has the government properly assessed the overall costs of delivering the power requirements for a Tier 3 data center?

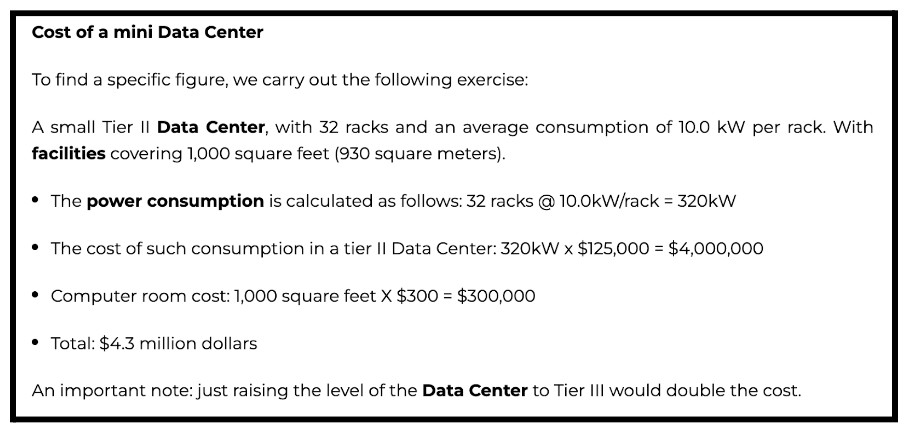

In addition, a Tier 3 data center requires the installation of redundant systems in terms of uninterrupted power (UPS), direct current battery plants, diesel-based power generators, and HVAC systems, including heating (H), ventilation (V) and precision air conditioning (AC). Below is an overview from Kio (a global data center company) in US dollars of the costs of building out such facilities.

With regards to network connectivity, a Tier 3 data center must have multiple Internet service provider connections and dedicated fiber optic cabling. This is particularly challenging as telecoms costs in Barbados are phenomenally high when compared to the global average. Furthermore, a mile of fiber optics can cost upwards of $250,000 USD. Then there are the incremental costs for perimeter control/fencing, access control systems, metal detectors, video monitoring, fuel tanks, telecoms grounding and lightning protection, fire suppression, racking hardware, networking equipment, server infrastructure, tier certification, etc. I will address the costs for staffing in greater detail in the next section.

The capital expenditure (CapEx) and operational expenditure (OpEx) can quickly skyrocket. My conservative estimation is CapEx of approximately USD$20 million for the greenfield build-out of the Tier 3 facility and USD$5-10 million in annual OpEx to successfully run it.

Taking into consideration that Tier 3 data centers usually have a commercial model, it would be good if the government can explain to the general public how the build-out is being funded, whether taxpayers will be expected to cover the costs, will more loans and increased debt be involved, how will the return on investment (ROI) be achieved, what does the total cost of ownership (TCO) look like over a 5-10 year period, and other related financing and cost recovery details.

Talent

Another area worth a deeper dive is the talent associated with the operations and maintenance of a Tier 3 data center. For operational sustainability, staffing must be divided into three (3) categories.

- Headcount: The number of personnel needed to meet the workload requirements for specific maintenance activities and shift presence. Assuming a 24x7x365 operation, headcount will be needed to cover daily administration, preventative maintenance, corrective maintenance, vendor support, project support, and tenant work orders.

- Qualifications: The degrees, certifications, technical training, and experience required to properly maintain and operate the wide array of installed infrastructure.

- Organization: The reporting structure for escalating issues or concerns, with roles and responsibilities defined for each group.

Most of the persons on-island that meet these requirements are employed by Digicel, Flow, or commercial banks. The remaining talent would have to be sourced from overseas. What is the government’s strategy for attracting and retaining this level of talent? How will they do so in a fiscally responsible manner? Has a skills gap analysis been performed for the public sector? Is there a talent management and professional development plan to ensure that this digital initiative is adequately resourced from the human capital perspective?

Environmental Impact

Data centers are responsible for an enormous negative environmental impact: their gluttonous annual consumption of electricity, greenhouse gas emissions, heavy water consumption, generation of toxic electronic waste, and other types of direct and indirect ecological harms are of a major concern. In conformity with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs), the potential environmental impact of data centers should be numerically assessed to compare to the environmental capacity and chart a plan towards sustainability.

Has the government completed an environment impact assessment (EIA) for the data center facility? Have they engaged surrounding residents to discuss the known issues with data centers, including noise pollution and drought risks? Given the government’s commitment to climate change, what are their plans for the Tier 3 facility vis-a-vis carbon-neutrality, carbon offsetting, and investment in renewable energy systems like wind and solar? What is the government’s broader toxic electronic waste disposal strategy?

The “Sovereign Cloud” Misnomer

The term “sovereign cloud” has been tossed around, but it appears to be more buzzword than substance. In the tech world, a sovereign cloud typically refers to public cloud services that treat workloads as if they’re in the client’s home country, even when physically hosted elsewhere. Sovereignty requirements mandate that customers’ usage of what’s typically understood as public cloud must be immune from the impact of foreign laws and mandates; sovereignty overall is then a key requirement for consideration alongside other controls requirements such as security, resilience, data residency, and privacy. These factors generally apply when a government or international organization is purchasing services from an overseas-based cloud provider.

What GovTech Barbados is proposing is simply a government-owned data center located on Bajan soil. It’s inherently sovereign, but a “sovereign cloud” it isn’t – it’s just a standard approach to local data hosting. By misusing this term, are they trying to make a normal infrastructure upgrade sound more innovative than it really is?

The vast majority of the government’s public sector computing environment is based on traditional client-server architecture and on-premise data processing. There’s nothing specifically “cloud-centric” about it. Bearing that in mind, it would be good to better understand the government’s future state cloud architecture. How will cloud-related skills be obtained in the public sector where they currently don’t exist? What’s the overall enterprise architecture model? How will they transform deeply antiquated, siloed and fragmented government systems into a cohesive architecture premised upon modern cloud technologies? What cloud solutions will be used for orchestration, observability, infrastructure, databases, etc.? How will existing infrastructure and applications be refactored to be cloud native? Is their approach based on private cloud, public cloud, or multi-cloud? Have disaster recovery needs been considered? Has the partner/vendor ecosystem been defined? What about third-party risk management (TPRM)? These questions and more need to be answered.

The last 2 questions are especially pertinent given the announced partnerships with Promotech and Fortinet – The former (Promotech) is a consumer electronics retailer with zero credentials in deploying complex, secure, enterprise-scale technologies and the latter (Fortinet), while a solid cybersecurity solutions vendor, requires advanced expertise to properly deploy and manage their equipment. Fortinet is also known to be quite expensive in terms of professional services and they have had a number of security issues in recent times.

Cybersecurity: Promises vs. Reality

The government’s emphasis on cybersecurity is not new. In fact, it’s a tune we’ve been hearing from as far back as 2012. Over the last 10 years, the Government of Barbados has received substantial funding from various international bodies to enhance its cybersecurity posture. Yet, where is our national cybersecurity unit? Why is our cybersecurity maturity so low compared to other developing countries such as Botswana, Cuba, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guyana, Jamaica, and Kenya, among others?

And despite numerous cybersecurity assessments, strategies, and roadmaps conducted by international organizations (e.g., ITU, OAS, European Commission, etc.), we seem no closer to establishing a robust cybersecurity framework than we were a decade ago.

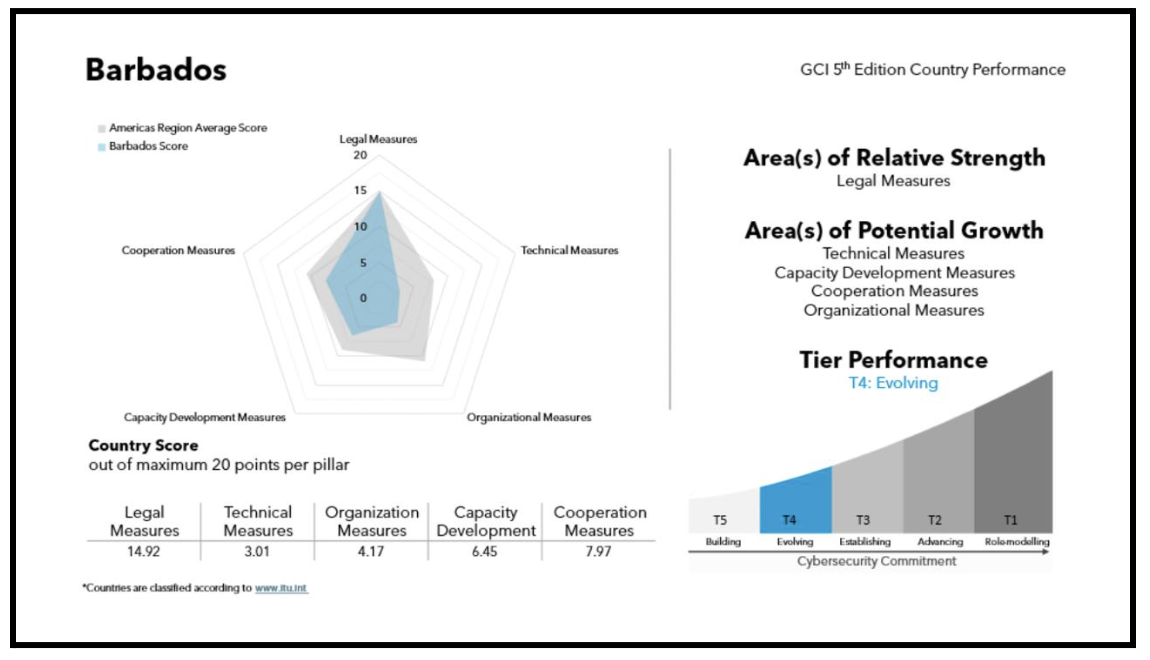

In the International Telecommunications Union’s (ITU’s) recently released 2024 Global Cybersecurity Index, Barbados scored quite poorly against the Americas regional average (see below).

With this ITU ranking as a backdrop, it has to be said that the GovTech Barbados announcement feels like déjà vu. What’s different this time? How can we trust that these plans will materialize when similar promises have fallen flat repeatedly? Amidst the talk of setting up a national cybersecurity unit, is Mr. Boyce aware that the responsibility for national cybersecurity lies with the Barbados Defence Force (BDF) Cyber Unit? Has he consulted with anyone on what was the mandate, scope, and lessons learned from the government’s failed Cyber Security Working Group (CSWG)? Has someone told him that in recent years, a Barbados Computer Emergency Response Team (BCERT) was funded by international donors, an office location and equipment was setup, but the CERT was never staffed or actually operational? To be frank, he seems quite unaware of what has transpired in the nation’s cybersecurity landscape over the past 5-7 years.

The Spectre of Abuse, Censorship, and Exclusion

While the government touts the benefits of centralized digital infrastructure, we must also consider its darker implications. A nationally controlled data center, pervasive e-government systems, and fully integrated identity-based platforms can easily become powerful tools for abuse of authority, mass surveillance, and oppression. These risks are even more pronounced with GovTech’s proposed use of artificial intelligence (with no regulatory safeguards) and the government’s insistence on implementing poorly drafted and potentially rights-violating cybercrime laws.

Myself and others have raised serious concerns, including worries about how new citizen-centered digital services are developed and managed; social exclusion and discrimination; privacy and data protection; cybersecurity; and major risks for human rights. In the context of human rights, the risks are related to the right to privacy, freedom of movement, freedom of expression, and other protected rights. For example, GovTech has stated that they plan on “releasing certain public datasets” in order “to spur the development of new products and services from local tech companies.” Government must be transparent on whether or not personal data will be involved and how these decisions align with the Data Protection Act, including what risk assessments and security countermeasures will be put into place to prevent material harm to individuals.

With all government data and services funneled through a single point, the temptation for overreach becomes significant. Who will oversee this system? What checks and balances will be in place to prevent abuse? The ability to control information flow and access to digital services could be weaponized against dissenting voices or used to manipulate public opinion.

We must demand clear, legally robust safeguards against such misuse. Without them, our journey towards digital transformation may well become a path to digital authoritarianism.

The Bigger Picture

While digital transformation is undoubtedly crucial for Barbados’ future, we must approach these grand declarations with healthy skepticism. Are we genuinely prepared for the scale of change being proposed? Do we have the necessary infrastructure, expertise, and, most importantly, the political will to see these projects through?

Moreover, in our rush to digitize, are we addressing more fundamental issues? Can we talk about advanced data centers when parts of our island still struggle with basic Internet connectivity? Are affordable Internet and telecoms services even attainable when the regulating functions within the Ministry of Industry, Information, Science and Technology (MIST) and the Fair Trading Commission (FTC) are incapable of delivering core consumer benefits (e.g., consumer protection, service quality, diverse product and services offerings, affordable prices, etc.)? Can we really talk about cybersecurity when breaches of government IT systems are the norm as opposed to the exception? Why are the bulk of e-government services still lacking in accessibility features for the differently abled?

Mr. Boyce emphasized that, “The National Data Centre will allow the government to take a more data-driven approach to governance.” Data centers and data governance are both important for the country’s data-driven future, but they have very different focuses, and the links between the two are tenuous. A data center is a physical facility that is used to house IT infrastructure, applications, and related data. Data centers are designed based on technology components: networks, computing, and storage resources that enable the delivery of shared applications and data. Data governance involves the management of data quality, security, usability, and availability. It is oriented towards people and processes – policies, procedures, roles, and metrics which ensure data is leveraged efficiently and effectively. Data governance can help the government and private corporations make better decisions, reduce costs, and comply with regulations such as the Data Protection Act (DPA), General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and others. However, one can have a data center and still have poor data governance or you can have no data center and have strong data governance. There are literally no dependencies of either element on the other.

“A key aspect of the digital transformation plan is to integrate digital services, allowing ministries and departments to collaborate seamlessly. Initiatives such as digital identifiers and signatures will enable citizens to access multiple services through a centralized portal, gov.bb, reducing fragmentation in the current system.” This statement from the CEO of GovTech is quite worrisome. Does he know that over the last 4 years there was an IDB-funded e-Services Project with these same objectives that failed spectacularly? Does he realize that the National Digital ID project – another public sector IT project that was poorly executed – was designed to provide centralized identity-based services to citizens, including digital identifiers and signatures?

The fact remains that IT projects for the Government of Barbados seldom fail due to technology-related issues. The technologies are generally sound and fit for purpose. Leadership-related issues are at the core of these repeated failures. A lack of skills in managing complex, large scale IT projects is also a major factor, which leads to a corresponding inclination to rely instead on outsourcing to consulting firms or a heavy dependence on the professional services arms of vendors. The problem here is that government employees lack the capabilities to manage these third-parties, are unable to meet government-owned deliverables, or impose unrealistic / infeasible requirements on experts that actually know what they’re doing. In addition to the absence of skills for managing large IT efforts in general, there are also huge deficiencies in change management skills in particular.

A Call for Transparency and Realism

As citizens, we deserve more than lofty promises and tech jargon. We need a clear, realistic roadmap for digital transformation that acknowledges our current limitations and outlines concrete steps to overcome them.

Instead of grand visions, let’s start with achievable goals. Develop a strategic roadmap that has a long-term arch and practicality that survives biased political motivations and changes in government administrations. Improve our basic digital infrastructure and access to it for all. Invest in education to build a tech-savvy workforce. Ensure that our legal and regulatory framework supports open, accessible, secure, rights upholding, and citizen-centric digital services. Create governance, risk, and oversight mechanisms which guarantee that projects deliver tangible value, not just headlines.

Barbados has the potential to become a digital leader in the Caribbean, but not through wishful thinking. We need honest assessments, pragmatic planning, and, above all, a commitment to turning words into action. Until then, these digital aspirations will remain just that – unfulfilled aspirations.